Linguistics is the scientific study of language.[1][2][3] The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds and equivalent gestures in sign languages), phonology (the abstract sound system of a particular language, and analogous systems of sign languages), and pragmatics (how the context of use contributes to meaning).[4] Subdisciplines such as biolinguistics (the study of the biological variables and evolution of language) and psycholinguistics (the study of psychological factors in human language) bridge many of these divisions.[5]

Linguistics encompasses many branches and subfields that span both theoretical and practical applications.[6] Theoretical linguistics is concerned with understanding the universal and fundamental nature of language and developing a general theoretical framework for describing it. Applied linguistics seeks to utilize the scientific findings of the study of language for practical purposes, such as developing methods of improving language education and literacy.

Linguistic features may be studied through a variety of perspectives: synchronically (by describing the structure of a language at a specific point in time) or diachronically (through the historical development of a language over a period of time), in monolinguals or in multilinguals, among children or among adults, in terms of how it is being learnt or how it was acquired, as abstract objects or as cognitive structures, through written texts or through oral elicitation, and finally through mechanical data collection or practical fieldwork.[7]

Linguistics emerged from the field of philology, of which some branches are more qualitative and holistic in approach.[8] Today, philology and linguistics are variably described as related fields, subdisciplines, or separate fields of language study, but, by and large, linguistics can be seen as an umbrella term.[9] Linguistics is also related to the philosophy of language, stylistics, rhetoric, semiotics, lexicography, and translation.

Major subdisciplines

Historical linguistics

Main article: Historical linguistics

Historical linguistics is the study of how language changes over history, particularly with regard to a specific language or a group of languages. Western trends in historical linguistics date back to roughly the late 18th century, when the discipline grew out of philology, the study of ancient texts and oral traditions.[10]

Historical linguistics emerged as one of the first few sub-disciplines in the field, and was most widely practised during the late 19th century.[11] Despite a shift in focus in the 20th century towards formalism and generative grammar, which studies the universal properties of language, historical research today still remains a significant field of linguistic inquiry. Subfields of the discipline include language change and grammaticalization.

Historical linguistics studies language change either diachronically (through a comparison of different time periods in the past and present) or in a synchronic manner (by observing developments between different variations that exist within the current linguistic stage of a language).[12]

At first, historical linguistics was the cornerstone of comparative linguistics, which involves a study of the relationship between different languages.[13] At that time, scholars of historical linguistics were only concerned with creating different categories of language families, and reconstructing prehistoric proto-languages by using both the comparative method and the method of internal reconstruction. Internal reconstruction is the method by which an element that contains a certain meaning is re-used in different contexts or environments where there is a variation in either sound or analogy.[13][better source needed]

The reason for this had been to describe well-known Indo-European languages, many of which had detailed documentation and long written histories. Scholars of historical linguistics also studied Uralic languages, another European language family for which very little written material existed back then. After that, there also followed significant work on the corpora of other languages, such as the Austronesian languages and the Native American language families.

In historical work, the uniformitarian principle is generally the underlying working hypothesis, occasionally also clearly expressed.[14] The principle was expressed early by William Dwight Whitney, who considered it imperative, a “must”, of historical linguistics to “look to find the same principle operative also in the very outset of that [language] history.”[15]

The above approach of comparativism in linguistics is now, however, only a small part of the much broader discipline called historical linguistics. The comparative study of specific Indo-European languages is considered a highly specialized field today, while comparative research is carried out over the subsequent internal developments in a language: in particular, over the development of modern standard varieties of languages, and over the development of a language from its standardized form to its varieties.[citation needed]

For instance, some scholars also tried to establish super-families, linking, for example, Indo-European, Uralic, and other language families to a hypothetical Nostratic language group.[16] While these attempts are still not widely accepted as credible methods, they provide necessary information to establish relatedness in language change. This is generally hard to find for events long ago, due to the occurrence of chance word resemblances and variations between language groups. A limit of around 10,000 years is often assumed for the functional purpose of conducting research.[17] It is also hard to date various proto-languages. Even though several methods are available, these languages can be dated only approximately.[18]

In modern historical linguistics, we examine how languages change over time, focusing on the relationships between dialects within a specific period. This includes studying morphological, syntactical, and phonetic shifts. Connections between dialects in the past and present are also explored.[19]

Syntax

Main article: Syntax

Syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, constituency,[20] agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning. There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals.

Morphology

Main article: Morphology (linguistics)

Morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language.[21][22] Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning. Morphemes include roots that can exist as words by themselves, but also categories such as affixes that can only appear as part of a larger word. For example, in English the root catch and the suffix -ing are both morphemes; catch may appear as its own word, or it may be combined with -ing to form the new word catching. Morphology also analyzes how words behave as parts of speech, and how they may be inflected to express grammatical categories including number, tense, and aspect. Concepts such as productivity are concerned with how speakers create words in specific contexts, which evolves over the history of a language.

The discipline that deals specifically with the sound changes occurring within morphemes is morphophonology.

Semantics and pragmatics

Main articles: Semantics and Pragmatics

Semantics and pragmatics are branches of linguistics concerned with meaning. These subfields have traditionally been divided according to aspects of meaning: “semantics” refers to grammatical and lexical meanings, while “pragmatics” is concerned with meaning in context. Within linguistics, the subfield of formal semantics studies the denotations of sentences and how they are composed from the meanings of their constituent expressions. Formal semantics draws heavily on philosophy of language and uses formal tools from logic and computer science. On the other hand, cognitive semantics explains linguistic meaning via aspects of general cognition, drawing on ideas from cognitive science such as prototype theory.

Pragmatics focuses on phenomena such as speech acts, implicature, and talk in interaction.[23] Unlike semantics, which examines meaning that is conventional or “coded” in a given language, pragmatics studies how the transmission of meaning depends not only on the structural and linguistic knowledge (grammar, lexicon, etc.) of the speaker and listener, but also on the context of the utterance,[24] any pre-existing knowledge about those involved, the inferred intent of the speaker, and other factors.[25]

Phonetics and phonology

Main articles: Phonetics and Phonology

Phonetics and phonology are branches of linguistics concerned with sounds (or the equivalent aspects of sign languages). Phonetics is largely concerned with the physical aspects of sounds such as their articulation, acoustics, production, and perception. Phonology is concerned with the linguistic abstractions and categorizations of sounds, and it tells us what sounds are in a language, how they do and can combine into words, and explains why certain phonetic features are important to identifying a word.[26]

Typology

This paragraph is an excerpt from Linguistic typology.[edit]

Linguistic typology (or language typology) is a field of linguistics that studies and classifies languages according to their structural features to allow their comparison. Its aim is to describe and explain the structural diversity and the common properties of the world’s languages.[27] Its subdisciplines include, but are not limited to phonological typology, which deals with sound features; syntactic typology, which deals with word order and form; lexical typology, which deals with language vocabulary; and theoretical typology, which aims to explain the universal tendencies.[28]

Structures

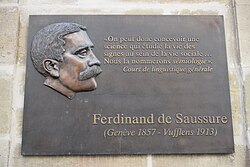

Linguistic structures are pairings of meaning and form. Any particular pairing of meaning and form is a Saussurean linguistic sign. For instance, the meaning “cat” is represented worldwide with a wide variety of different sound patterns (in oral languages), movements of the hands and face (in sign languages), and written symbols (in written languages). Linguistic patterns have proven their importance for the knowledge engineering field especially with the ever-increasing amount of available data.

Linguists focusing on structure attempt to understand the rules regarding language use that native speakers know (not always consciously). All linguistic structures can be broken down into component parts that are combined according to (sub)conscious rules, over multiple levels of analysis. For instance, consider the structure of the word “tenth” on two different levels of analysis. On the level of internal word structure (known as morphology), the word “tenth” is made up of one linguistic form indicating a number and another form indicating ordinality. The rule governing the combination of these forms ensures that the ordinality marker “th” follows the number “ten.” On the level of sound structure (known as phonology), structural analysis shows that the “n” sound in “tenth” is made differently from the “n” sound in “ten” spoken alone. Although most speakers of English are consciously aware of the rules governing internal structure of the word pieces of “tenth”, they are less often aware of the rule governing its sound structure. Linguists focused on structure find and analyze rules such as these, which govern how native speakers use language.

Grammar

Grammar is a system of rules which governs the production and use of utterances in a given language. These rules apply to sound[29] as well as meaning, and include componential subsets of rules, such as those pertaining to phonology (the organization of phonetic sound systems), morphology (the formation and composition of words), and syntax (the formation and composition of phrases and sentences).[4] Modern frameworks that deal with the principles of grammar include structural and functional linguistics, and generative linguistics.[30]

Sub-fields that focus on a grammatical study of language include the following:

- Phonetics, the study of the physical properties of speech sound production and perception, and delves into their acoustic and articulatory properties

- Phonology, the study of sounds as abstract elements in the speaker’s mind that distinguish meaning (phonemes)

- Morphology, the study of morphemes, or the internal structures of words and how they can be modified

- Syntax, the study of how words combine to form grammatical phrases and sentences

- Semantics, the study of lexical and grammatical aspects of meaning[31]

- Pragmatics, the study of how utterances are used in communicative acts, and the role played by situational context and non-linguistic knowledge in the transmission of meaning[31]

- Discourse analysis, the analysis of language use in texts (spoken, written, or signed)

- Stylistics, the study of linguistic factors (rhetoric, diction, stress) that place a discourse in context

- Semiotics, the study of signs and sign processes (semiosis), indication, designation, likeness, analogy, metaphor, symbolism, signification, and communication

Discourse

Discourse is language as social practice (Baynham, 1995) and is a multilayered concept. As a social practice, discourse embodies different ideologies through written and spoken texts. Discourse analysis can examine or expose these ideologies. Discourse not only influences genre, which is selected based on specific contexts but also, at a micro level, shapes language as text (spoken or written) down to the phonological and lexico-grammatical levels. Grammar and discourse are linked as parts of a system.[32] A particular discourse becomes a language variety when it is used in this way for a particular purpose, and is referred to as a register.[33] There may be certain lexical additions (new words) that are brought into play because of the expertise of the community of people within a certain domain of specialization. Thus, registers and discourses distinguish themselves not only through specialized vocabulary but also, in some cases, through distinct stylistic choices. People in the medical fraternity, for example, may use some medical terminology in their communication that is specialized to the field of medicine. This is often referred to as being part of the “medical discourse”, and so on.

Lexicon

The lexicon is a catalogue of words and terms that are stored in a speaker’s mind. The lexicon consists of words and bound morphemes, which are parts of words that can not stand alone, like affixes. In some analyses, compound words and certain classes of idiomatic expressions and other collocations are also considered to be part of the lexicon. Dictionaries represent attempts at listing, in alphabetical order, the lexicon of a given language; usually, however, bound morphemes are not included. Lexicography, closely linked with the domain of semantics, is the science of mapping the words into an encyclopedia or a dictionary. The creation and addition of new words (into the lexicon) is called coining or neologization,[34] and the new words are called neologisms.

It is often believed that a speaker’s capacity for language lies in the quantity of words stored in the lexicon. However, this is often considered a myth by linguists. The capacity for the use of language is considered by many linguists to lie primarily in the domain of grammar, and to be linked with competence, rather than with the growth of vocabulary. Even a very small lexicon is theoretically capable of producing an infinite number of sentences.

Vocabulary size is relevant as a measure of comprehension. There is general consensus that reading comprehension of a written text in English requires 98% coverage, meaning that the person understands 98% of the words in the text.[35] The question of how much vocabulary is needed is therefore related to which texts or conversations need to be understood. A common estimate is 6-7,000 word families to understand a wide range of conversations and 8-9,000 word families to be able to read a wide range of written texts.[36]

Style

Stylistics also involves the study of written, signed, or spoken discourse through varying speech communities, genres, and editorial or narrative formats in the mass media.[37] It involves the study and interpretation of texts for aspects of their linguistic and tonal style. Stylistic analysis entails the analysis of description of particular dialects and registers used by speech communities. Stylistic features include rhetoric,[38] diction, stress, satire, irony, dialogue, and other forms of phonetic variations. Stylistic analysis can also include the study of language in canonical works of literature, popular fiction, news, advertisements, and other forms of communication in popular culture as well. It is usually seen as a variation in communication that changes from speaker to speaker and community to community. In short, Stylistics is the interpretation of text.

In the 1960s, Jacques Derrida, for instance, further distinguished between speech and writing, by proposing that written language be studied as a linguistic medium of communication in itself.[39] Palaeography is therefore the discipline that studies the evolution of written scripts (as signs and symbols) in language.[40] The formal study of language also led to the growth of fields like psycholinguistics, which explores the representation and function of language in the mind; neurolinguistics, which studies language processing in the brain; biolinguistics, which studies the biology and evolution of language; and language acquisition, which investigates how children and adults acquire the knowledge of one or more languages.

Approaches

See also: Theory of language

Humanistic

The fundamental principle of humanistic linguistics, especially rational and logical grammar, is that language is an invention created by people. A semiotic tradition of linguistic research considers language a sign system which arises from the interaction of meaning and form.[41] The organization of linguistic levels is considered computational.[42] Linguistics is essentially seen as relating to social and cultural studies because different languages are shaped in social interaction by the speech community.[43] Frameworks representing the humanistic view of language include structural linguistics, among others.[44]

Structural analysis means dissecting each linguistic level: phonetic, morphological, syntactic, and discourse, to the smallest units. These are collected into inventories (e.g. phoneme, morpheme, lexical classes, phrase types) to study their interconnectedness within a hierarchy of structures and layers.[45] Functional analysis adds to structural analysis the assignment of semantic and other functional roles that each unit may have. For example, a noun phrase may function as the subject or object of the sentence; or the agent or patient.[46]

Functional linguistics, or functional grammar, is a branch of structural linguistics. In the humanistic reference, the terms structuralism and functionalism are related to their meaning in other human sciences. The difference between formal and functional structuralism lies in the way that the two approaches explain why languages have the properties they have. Functional explanation entails the idea that language is a tool for communication, or that communication is the primary function of language. Linguistic forms are consequently explained by an appeal to their functional value, or usefulness. Other structuralist approaches take the perspective that form follows from the inner mechanisms of the bilateral and multilayered language system.[47]

Biological

Further information: Biolinguistics and Biosemiotics

Approaches such as cognitive linguistics and generative grammar study linguistic cognition with a view towards uncovering the biological underpinnings of language. In Generative Grammar, these underpinning are understood as including innate domain-specific grammatical knowledge. Thus, one of the central concerns of the approach is to discover what aspects of linguistic knowledge are innate and which are not.[48][49]

Cognitive linguistics, in contrast, rejects the notion of innate grammar, and studies how the human mind creates linguistic constructions from event schemas,[50] and the impact of cognitive constraints and biases on human language.[51] In cognitive linguistics, language is approached via the senses.[52][53]

A closely related approach is evolutionary linguistics[54] which includes the study of linguistic units as cultural replicators.[55][56] It is possible to study how language replicates and adapts to the mind of the individual or the speech community.[57][58] Construction grammar is a framework which applies the meme concept to the study of syntax.[59][60][61][62]

The generative versus evolutionary approach are sometimes called formalism and functionalism, respectively.[63] This reference is however different from the use of the terms in human sciences.[64]

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment